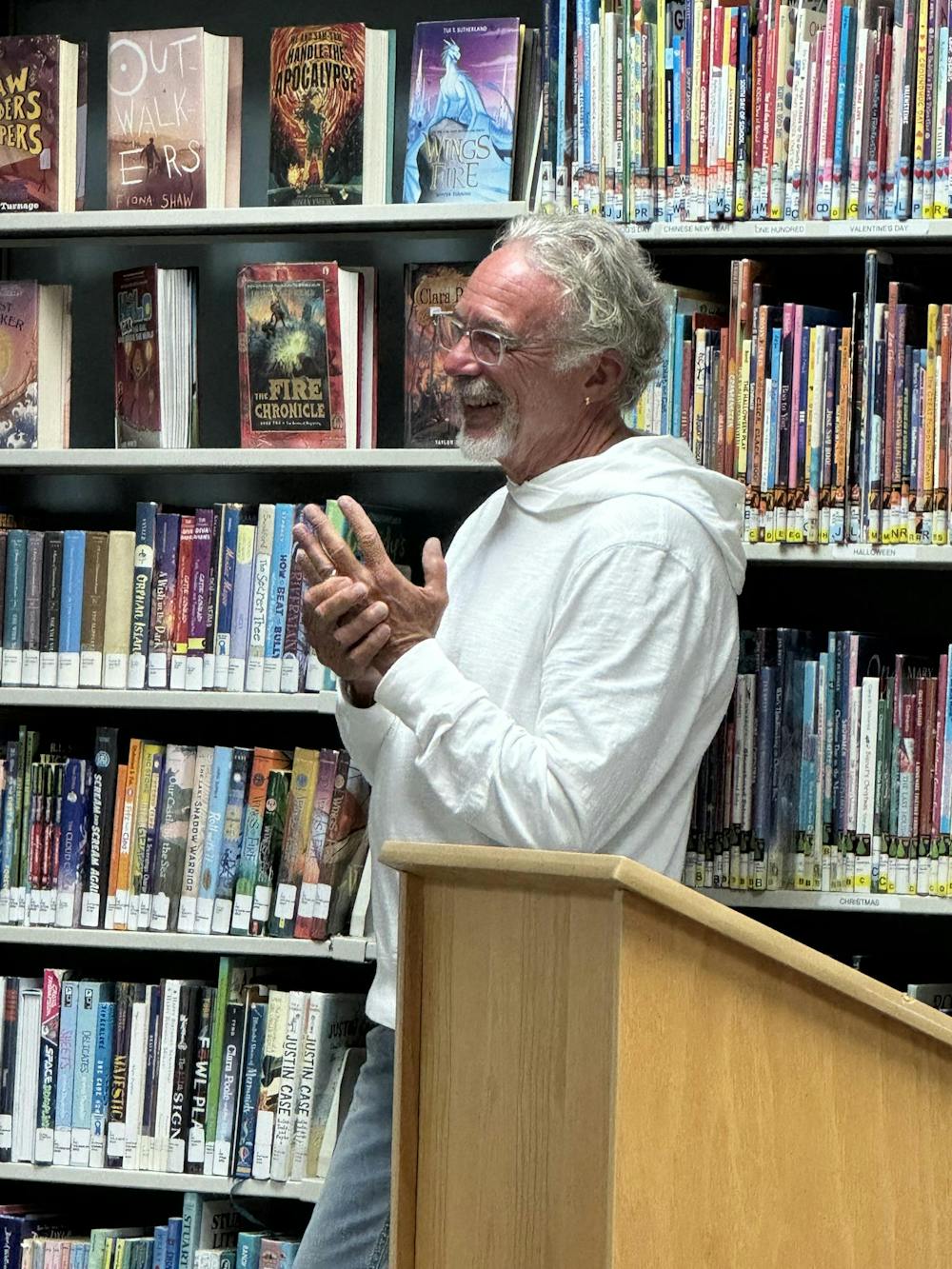

On Monday, August 18, the Pentwater Township Library invited the public to a presentation on “Microplastics and the Great Lakes” by Art Hirsch. A native of Muskegon, Hirsch is a retired professor and environmental engineer who graduated from Michigan State University and the University of Colorado. Busy year-round as an advocate for fewer plastics in the environment, he spends his summers in the Pentwater area and he welcomed the opportunity to speak locally.

”I’m here to entertain you and to educate you,” he told the audience. He carried the interest of the standing-room-only crowd so that they stretched his scheduled 45-minute time slot past the 75-minute mark.

“Every year 22 million pounds of plastic enter the Great Lakes, especially Lake Michigan. Plastic is a real risk, not a potential risk,” he asserted. “It is found in people and in animals. Plastic is not biodegradable, and recycling will not solve our problem. Plastic simply breaks down into smaller pieces for its next life. Microplastics are 3/16-inch-sized (or less) pieces of plastic, and nanoplastics are smaller yet pieces resulting from the breakdown of microplastics.”

Autopsies of Great Lakes fish clarify the damage. The fish see the microplastics in the water and think that it’s food. They eat it and feel full because it does not digest easily, which keeps them from eating more. Without the nutrition they need, the fish starve to death. A similar story is true with birds.

Microplastics are also found in human beings. Hirsch reported, “It is estimated that humans ingest 0.1 to a maximum of 5 grams of plastic weekly. Five grams would be the equivalent of a credit card. Research has shown that plastics have a negative impact on multiple systems: the endocrine, the cardiovascular, the immune and the reproductive systems and the brain.” He said that it is contacted through the skin (clothing and cosmetics), by inhalation and by ingestion from water and food.

It is important to be aware of how many products one uses regularly that contribute to the risks associated with plastics and the challenge of managing plastic waste, Hirsch asserted. “One-time use plastic products are the worst problem because they are immediately discarded.”

Other culprits include manufacturing chemicals, abrasives in cleaning products, paint, cigarette filters, construction trades (the mantra “vinyl is final” is true in more ways than one), in the packaging of products such as dishwasher tabs and laundry soap pods, and in the wrapping of produce at the grocery store.

How does plastic find its way into the environment? One-time-use plastics, film and styrofoam are obvious ways, but other ways are subtle, he explained, and then gave numerous examples. Motor vehicles have microplastics in their tires, and the friction caused by contact with the road surface sends microplastic material into the air or into water runoff. The spin cycles of laundry machines cause the release of microplastics in synthetic textiles, of which fleece is most guilty - witnessed by the lint collected. Wastewater treatment plants create a sludge with materials filtered out of the water, which is often used as fertilizer for agricultural purposes, allowing it to re-enter the environment.

Every attempt to recycle plastic gives it new life elsewhere. Even in landfills where efforts are made to keep waste from entering the soil, nothing offers a foolproof guarantee against seepage through any protective coverings, Hirsch said.

”Enough with the doom and gloom,” Hirsch said after presenting the aforementioned information. “What can we do about it?”

Personally, he said that people can avoid drinking beverages from plastic bottles or heating food in plastic containers in the microwave; take groceries home in paper, fabric or reusable bags; wear clothing made from natural textiles like cotton or wool instead of synthetic textiles; use detergents in powder or liquid form instead of in plastic pods; and read labels on food and other purchases to avoid plastic additives.

Locally, people can install rain gardens and landscape buffers around water sources to help create clean drinking water. One can also look into supporting efforts to develop filters for washing machines and for motor vehicles to capture microplastics.

“Unfortunately, the state of Michigan has done nothing to alter the situation. Several proposed laws in the last couple years have been defeated in Lansing,” Hirsch said. “But there are some encouraging movements in other states. California is the primary leader, but Wisconsin, Illinois and New York are also actively working on the problem. Colorado has actually passed legislation to eliminate one-time-use plastics completely and given companies three years to comply. The only federal law to impact the situation was in 2015, when controls were established on cosmetic products that were exfoliants.”

He did share one encouraging word about Michigan. “A $2 million grant was given to EGLE to start monitoring surface and drinking water.”

Please visit the Pentwater Township Library for more information about this presentation.